What is the effect of digitalization on jobs and the economy? These are question posed in a report presented to the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise today. The author of the report is Mårten Blix, an independent consultant and also former secretary in the previous government’s inquiry “Commission on the Future Challenges for Sweden.” Sweden has a strong standing among the technological leaders in digitalization but other countries are catching up. As one of the few countries in Europe with sound fiscal finances, one danger lies in political complacency. Digitalization presents challenges to the core of the welfare state – the financing of public welfare, income distribution and high levels of employment. Already now, public welfare services are under increasing cost pressures from aging populations. “There is no room to raise taxes if Sweden is to remain competitive,” says Mårten Blix. “With high taxes on labor and one of the most highly regulated housing markets, there is a risk that new jobs and services will grow too slowly and that people cannot move to where the jobs are. Job automation and transfer of tasks to the cloud will put increasing pressures on a tax base in large part based on labor income,” says Mårten Blix. Moreover, the highly regulated labor market with high entry barriers makes it difficult for unskilled workers to get jobs. As the work force ages, life-long learning will be a key ingredient to retain competitiveness. The rise of the sharing economy will also help provide flexibility of work and better use of resources. Many OECD-countries have experienced shrinking middle classes with increased polarization, partly driven by technology. Sweden differs in this development in that the shares of lower paid job have remained about the same while the higher paid jobs have increased. “Digitalization may bring job and wage polarization also to Sweden in the years ahead,” says Mårten Blix. “There is nothing inevitable how well the welfare state will cope with digitalization and the outcomes will depend on the choices of political institutions.” “The risks associated with freelance work should also be addressed in the social security systems, not by according employment status but by reducing the inherent asymmetries that favor employees over the self-employed,” says Mårten Blix. “The biggest danger now is a protectionist response or a policy of ‘muddling through’. If the legal and regulatory obstacles are not addressed, the benefits of digitalization will be slower in coming while the negative labor market effects may be real enough. The results would be worse on all fronts: slower productivity growth, higher risks of technological unemployment, and rising inequality.” In the report, some specific policies are proposed that would help smooth adjustment in the labor market and help realize the benefits of digitalization:

About the author: Mårten Blix has PhD in Economics from Stockholm University and an MSc in Econometrics and Mathematical Economics from the London School of Economics. He has held several senior positions in the Swedish Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Industry and also at the Swedish Central Bank (the Riksbank). He was also secretary in the previous government’s “Commission on the Future Challenges of Sweden,” in which he wrote a report for the Prime Minister on “Future Welfare and the ageing population.” He is now an independent consultant and guest researcher at the Research Institute for Industrial Economics in Sweden, www.ifn.se. He is currently working on a book on “Digitalization and Challenges for the Welfare State.”

4 Comments

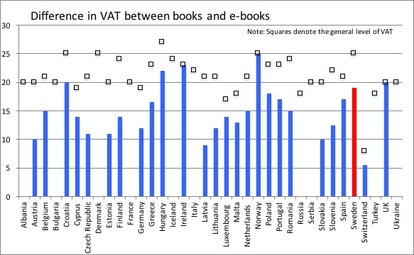

In most instances regulatory obstacles and hurdles are not black or white, there is usually some argument that supports even strange rules. When it comes to VAT differences between print and e-books, however, it is exceedingly hard to find even the faintest rationale. Reading a book or an e-book are arguably just different ways to consume the same good. For countries in Europe, the figure below shows the differences in VAT on books and e-books in the vertical bars, along with the general level of VAT. Overall, the price difference is quite significant in Europe. Although only a few countries have no differences and a fairly low applicable VAT, such as France, Iceland, and Italy, most other countries have considerable differences. Ireland has one of the largest discrepancies at 23 percentage points, with zero VAT on print books but 23 percent on e-books; Denmark has the same VAT for both media, but at the high rate of 25 percent. The median difference in VAT is just over 12 percentage points. In Sweden, the difference is 19 percentage points. For the 79 countries covered in the survey, 35 apply a higher rate of VAT to e-books than to print books. Note: The bars show the difference between VAT on print books compared to e-books. Some countries have no difference (and hence the bar is at zero, in Italy, for example). The square indicates the general VAT level in that country. Source: International Publishers Association (2015). “VAT/GST on Books & E-books.” An IPA/FEP Global Special Report. July 2015. Varning: denna korrelation kan vara skadlig för din hälsa! Eller leda till felaktig policy…12/3/2015 Big data kommer göra det möjligt att beräkna korrelationer på alla möjliga områden och använda resultaten för prognoser eller policy analys. Utvecklingen är mer eller mindre oundviklig men inte odelat bra. Det finns nya faror som kan leda till allvarliga fel.

En risk som kan uppstå är att förväxla korrelation med kausalitet när man fattar affärsbeslut eller analyserar policy. De enorma mängderna med data om konsumenttrender, livsstilar och nätvanor är värdefulla för företagen och ger tillgång till information som kan användas till att nå specifika grupper med reklam och försäljningsargument. När det gäller policy finns det mängder med värdefulla data om människors beteende som kan ge beslutsfattarna en bild av människors reaktioner på skattereformer eller andra förändringar. En oemotståndlig lockelse kan vara att låta de enorma datamängderna ge upphov till bedömningar som förefaller att vara mycket exakta. Stora datamängder innebär vanligen mindre osäkra mätningar och mätningar på hela populationen eliminerar all stickprovsosäkerhet. Allt fler företag har tillgång till big data eller säljer åtkomst till big data. Men den synbarliga precisionen från sådana analyser kan vara falsk och kanske inte tål en förändring av förutsättningarna. De som utför kvantitativa studier behöver vara försiktiga med att inte tolka korrelationer som kausala samband. Erfarenheterna från Google, som förutsåg en influensaepidemi med hjälp av sökfrekvenser, är ett bra exempel på hur bräckliga korrelationer kan vara.[1] När förhållandena förändras kan konsumenternas beteende också förändras. Riskerna med vantolkning av korrelationer ökar om de är stabila under lång tid och sedan plötsligt förändras på grund av en oförutsedd händelse. Banker som tillhandahöll lån i USA före finanskrisen förutsåg framtida risker med hjälp av enorma mängder data om tidigare tvångsförsäljningar av fastigheter. Men de omfattande problemen med s.k. sub-prime lån, som visserligen var en en liten del av den totala marknaden, skapade sedan en dominoeffekt till resten av marknaden, och de historiska korrelationerna var som bortblåsta. Samma sak kan hända med konsumentundersökningar och andra analyser som baseras på big data. Konsekvenserna av att anta att det finns kausalitet, trots att den inte existerar, är inte bara ett rent akademiskt felsteg, det kan få allvarliga ekonomiska följdverkningar och även leda till felaktiga affärsbeslut. Ett exempel som visar var sådana risker finns är det nya fenomenet "now-casting" (nutidsprognoser), som använder enorma mängder data från webben (bl.a. om människors sökvanor) som indata för makroekonomiska prognoser. Ett exempel: är fler sökningar efter arbetslöshetsunderstöd på nätet ett tecken på att arbetslösheten kommer att öka? En sådan korrelation kan se trovärdig ut, men människors beteenden kan förändras över tid så att korrelationen blir svagare, som i exemplet med Google och influensaepidemin. Slutsatsen är inte att korrelationerna saknar värde men att de bör kombineras med andra typer av data och modeller för att stödja de slutsatser som dras. [1] Se Lazer, David, Ryan Kennedy, Gary King and Alessandro Vespignani (2014). “The Parable of Google Flu: Traps in Big Data Analysis.” Science 343(6176). 1203–1205. Big data will make it possible to find correlations in all sorts of areas and use them for forecasting and policy analysis. This is inevitable but not wholly a good thing. There are new dangers that lurk for the unwary.

There is a serious risk of mistaking correlations for causality when making business decisions or conducting policy analysis. The huge amounts of data available on consumer trends, lifestyles, and online habits are valuable to firms and provide information that can be used to target specific groups through advertising and sales pitches. In relation to policy, there is a vast trove of behavior data available that can inform policymakers how people will react to tax changes or other changes. The irresistible lure may be that the huge amounts of data provide seemingly precise estimates. Large data sets typically imply less uncertain measurement and when the whole population is measured, there is no remaining sampling uncertainty. More and more firms have access to big data or sell access to big data. But the apparent precision of such analysis may be a castle built on sand and may not withstand a change in conditions. Those conducting empirical work needs to be mindful to not interpret correlations as showing causality. The experience with Google that used search frequencies to predict the onset of flu is an illustration of how fragile correlations can be.[1] When conditions change, consumer behavior can change. The danger of over-interpreting correlations is aggravated by that correlations can be stable for a long time and change only suddenly to due some unforeseeable trigger. For example, banks that provided loans in the US prior to the financial crisis used vast amounts of past foreclosure data to predict future risk. But the many sub-prime foreclosures, while very small compared to the total market, created a domino effect that cascaded into the rest of the market, blowing historical correlations into the trashcan. The same may happen to consumer surveys and other analysis based on big data. The consequences of presuming causality when none exists is thus not one of an academic faux pas; it can have serious economic consequences on society and lead to bad business decisions. One example of where this danger lurks is in the rising area of “now-casting,” using vast hoards of online data (such as people’s search habits) as input for macroeconomic forecasts. For example, do more online searches for unemployment benefits imply unemployment may be on the rise? Such a correlation may quite possibly seem strong, but just as with the Google flu, people’s behavior may alter over time and the correlation become weaker. The point is not to deny the value of drawing inferences from online searches but to highlight the importance of combining it with other types of corroborating data and models. [1] See Lazer, David, Ryan Kennedy, Gary King and Alessandro Vespignani (2014). “The Parable of Google Flu: Traps in Big Data Analysis.” Science 343(6176). 1203–1205. tt redigera. In an upcoming report on 15 dec available on www.martenblix.com, I will discuss the effects of digitalization on a modern economy, such as Sweden.

The effects on modern economies will likely be far reaching, but the disruptive forces may be even stronger for countries in Asia, see recent article in by Kathy Chu and Bob Davis in the Wall Street Journal. China was able to leapfrog several steps in technological development and was not inhibited by having old systems in place or the need to cater to political forces the way democratic countries must. As a result, some southeast Asian countries have more modern capital stock and infrastructure than many OECD countries. In the last decades of this rapid development, southeast Asian countries have benefited from work outsourced from OECD countries, all from manufacturing of iPhones to support centers or software development. With plenty of cheap labor available, outsourcing was attractive and allowed global companies to keep costs low. The same logic of keeping costs low may now lead to a wave of reshoring – manufacturing of electronics and other products may return to OECD countries but in the form of jobs for robots instead of people, especially as labor costs in some of those countries have been rising. If jobs in manufacturing and textiles are indeed reshored, the upheaval in southeast Asia may be considerable. With little or no social safety nets, the unskilled workers in factories will find it hard to find other work. Also, the political processes that may have prevented some of the outsourcing from OECD countries may even accelerate this process. There is a risk that reshoring may be much more disruptive for developing countries without adequate social safety nets than outsourcing was in the OECD. It is sometimes said of China that it may grow old before it grows rich; reshoring due to digitalization may intensify this trend. As expressed by Dani Rodrik, professor at Harvard University, the emerging world may have to cope with “premature industrialization” or, with regard to India, in the words of Raghuram Rajan, now governor of the Bank of India and former Chief Economist of the IMF, “premature non-industrialization,” discussed in the Economist last year. This captures the challenge of having a manufacturing base without other functioning features of economies in the developed world, especially services. Should manufacturing in China and emerging economies become uncompetitive, there are too few other exports to support growth. |

Mårten BlixI will write comments on digitalization and other other economic issues here Archives

March 2017

Categories |

Copyright Mårten Blix 2023

RSS Feed

RSS Feed